Cue Sheet – 2008

posted by James Reel

My organization, the Arizona Friends of Chamber Music, has booked the Guarneri Quartet for an April concert here in Tucson, one of its very last before it disbands. But second violinist John Dalley has been diagnosed with prostate cancer, and will soon undergo treatment, which will of course disrupt the quartet's tour schedule. For a good short news item on the subject, see this from the online version of Strings magazine. (By the way, that line about the group being featured in the February issue is a reference to a big article by yours truly.)

According to the Guarneri's management, the Tucson date should not be affected. Here's the message we got: "Commencing January 15, some February performance dates are currently being rescheduled. ... Your concert on April 22 will take place as scheduled. Only some dates in second half of February are affected."

That's good news for us in Tucson, and I do hope that eventually John Dalley will have good news as well. At least prostate cancer is one cancer whose treatment has a high success rate.

Classical Music,

November 21st 2008 at 10:21 —

c (0) —

K

f

g

k

posted by James Reel

Sometimes I worry (but only for a moment) about over-exposure. Yesterday a magazine editor sent me 13 assignments due at various points between now and next September, in addition to assignments I already have for that magazine, and others that are sure to follow. How much of me can editors and readers really stand in a single issue? And in the latest Tucson Weekly, I make a perhaps excessive three contributions.

First, a review of a murder mystery at Live Theatre Workshop:

A body lies just within the gates of an estate owned by a rather reclusive and no-longer-wealthy woman and her brooding son.

Was the victim--the household maid--killed by the mother, who feared that the maid's sexual allure would threaten the son's impending marriage into a wealthy family? Was she killed by the son, a dark and perhaps unstable fellow who may have been having an affair with her? Or was she murdered by the manipulative and coarse chauffeur? Or by one of any number of other people within or outside the mansion?

This is the stuff of classic murder mysteries, and specifically, it's the situation in George Batson's _Design for Murder_, a 1930s whodunit in the style of Agatha Christie, but with better fleshed-out characters.

Oddly, now that I've seen Live Theatre Workshop's production of the play, I know the identity of the murderer, but I honestly can't remember the true motive for the killing …

You’ll find the full review here, before rolling merrily along to my account of a Sondheim mounting:

To wed or not to wed?

That is the question for 35-year-old Robert, an inveterate bachelor whose friends are all married couples. He doesn't have a compelling reason for nuptials; his friends aren't the best practitioners of marriage, and he's not fully committed to any of the three women he's dating. But neither does he have a compelling reason to avoid marriage; at the very least, a wife would provide him with company--as if his friends didn't already give him all the company he needed.

_Company_ is the early-'70s stage work with book by George Furth and music and lyrics by Stephen Sondheim that set the course for a new kind of entertainment: the concept musical. Here, the psychology and situations of the characters were explored in depth, while linear plot fell by the wayside. _Company_ wasn't the first show to do this (_Hair_, for example, was an important precursor, and you can see that soon at Arizona Theatre Company), but it was the first concept musical to seduce the critics and attract a serious audience. (Serious not being synonymous with large.)

Is _Company_ too dated of a show to be presented, as it is right now, by the UA's Arizona Repertory Theatre? Well, the '70s are still recent enough to be a source of both nostalgia and embarrassment--check out the vintage TV commercials and PSAs screened onstage as the audience settles in, not to mention Nicholas Halder's pitch-perfect, skin-tight costumes. But beneath the surface, and beyond the comedy of manners made possible by the then still-novel sexual revolution, _Company_ explores relationship issues that remain relevant.

The full review lurks here. Then, over in the Chow section, I cover a restaurant that has good food but suffers from inattention to certain details, and a general lack of focus:

Tapas started out as Spanish bar snacks, small portions of all sorts of things--olives and cheese, sautéed potatoes, deep-fried squid, or whatever Spaniards felt like nibbling on to hold themselves together until their full late-night dinner.

Variety is key to the tapas experience. Angelina's Ristorante in Oro Valley has seized on the idea of variety and taken it to extremes--not just in the menu, but in its very identity. Angelina's primary purpose seems to be sit-down tapas meals, but it's also a martini lounge (more than 60 concoctions, plus the usual cocktail, beer and wine options), a pizza palace (about 60 varieties) and a sports bar. Its concept is the embodiment of those extravagant dishes you find at high-end restaurants that mingle all sorts of flavors you wouldn't expect to be compatible (and sometimes aren't).

Angelina's would offer a more satisfying dining experience if it didn't try to be so many different things, and I would advise the owners to ditch the sports-bar element. …

I’ve already gotten a semi-literate, marginally coherent e-mail objecting to the review from someone who seems not to have actually read it. Apply your superior brain power here.

tucson-arts,

November 20th 2008 at 9:31 —

c (0) —

K

f

g

k

posted by James Reel

If you enjoyed seeing and hearing mezzo Stephanie Blythe in Arizona Opera’s production of The Mikado over the weekend, you’ll be happy to hear that Musical America has named her vocalist of the year. The honor, as usual, seems to recognize ongoing achievement rather than any particular accomplishments during the past 12 months. Here’s what the press release says about her:

“Mezzo-soprano Stephanie Blythe is a singer of extraordinary versatility, an artist who makes the most difficult challenges seem easy, with a big, warm, well-balanced tone throughout an exceptional range. Her latest roles in 15 years at the Metropolitan Opera will be Gluck’s Orfeo in January and Jezibaba in Dvorák’s _Rusalka_ in March, and next summer she sings the roles of Fricka and Waltraute in Seattle Opera’s production of Wagner’s Ring cycle.”

You can read a compact bio of her here, and find out who else got the nod from Musical America here.

Classical Music,

November 19th 2008 at 8:14 —

c (0) —

K

f

g

k

posted by James Reel

If you’re enjoying our Thursday broadcasts of the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center, you might be interested in reviews of a couple of the organization’s downloads I wrote for Fanfare magazine:

BARTÓK Contrasts DVORÁK Piano Quintet in A, Op. 81 Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 477 7073 (digital download only; available at www2.deutschegrammophon.com and www.iTunes.com: 58:07)

DEBUSSY AND THE MODERNS Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 477 6627 (digital download only; available at www2.deutschegrammophon.com and www.iTunes.com: 95:50)

DEBUSSY Sonatas: for Flute, Viola, and Harp; for Cello and Piano; for Violin and Piano STUCKY _Sonate en Forme de Preludes_ SAARIAHO _Je sens un deuxième Coeur (I Feel a Second Heart)_ DALBAVIE _Axiom_

These two early items in the DG Concerts series of downloads (not available on disc) have been available for more than a year, but they’re still worth bringing to your attention, particularly the Debussy project. I’ve coupled them in a single review because if you prefer to transfer your downloads to disc rather than just play them from your hard drive or mp3 device, they fill up a pair of CDs nicely, whereas the first program is too short for one disc and the other is too long.

I’ll make quick work of the first pairing. Contrasts, played by Erin Keefe, Jose Franch-Ballester, and Gilles Vonsattel, benefits from a sometimes bluesy feel in the violin and properly acerbic playing in the clarinet’s high register; the finale has lots of paprika. The Dvorák (performed by Yoon Kwon, Erin Keefe, Beth Guterman, Efe Baltacigil, and Wu Han) receives an ardent performance but one not as high-strung as American ensembles can be these days. The cellist plays with a singing tone, and pianist Wu Han offers many pearly passages. There’s gentle animation where needed in the slow movement, the third balances playfulness with lyricism, and the final movement begins as a scamper, then gradually builds force and power. Both performances hold up very well against the competition, although detailed comparisons seem a bit beside the point if you’re downloading this material for casual listening.

In 1915, Claude Debussy planned to pay tribute to his French Classical forebears (they were really Baroque, but the French hated that term) with a set of six sonatas for diverse instruments. He lived to complete only three, masterpieces all; early in this century, a consortium including the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln center asked three of today’s leading composers to complete the project, using Debussy’s instrumentation but writing in their own style. The new pieces were premiered in 2004, but not until two years later were they presented in the context of Debussy’s own work, and this is a recording of that concert. Each of the new pieces follows one of Debussy’s sonatas, providing many opportunities for comparison and contrast, particularly of how the four composers approach timbre.

At this point, with many recordings of the Debussy sonatas already available, the new works are of greatest interest, so I’ll begin there. Debussy set a real challenge in planning a sonata for harpsichord, oboe, and horn, and Steven Stucky took it on in the form of brief preludes that tend to keep the oboe and horn isolated from each other, not overwhelming the harpsichord. Interestingly, the presence of the harpsichord does not lead Stucky down the Neoclassical path; he offers essentially a series of short conversations between the blown instruments, with the harpsichord indulging in rolled chords and lots of passagework that never sounds like “sewing-machine music.” Each movement has a fanciful title, and the musical material ranges from the largely static “Pierrot Hides in the Shadows” to the comparatively hyperactive “Fireworks.”

One of today’s experts in timbrel possibility is surely Kaija Saariaho, yet she was assigned the relatively conventional combination of piano, viola, and cello. The odd movements in this five-movement suite are nocturnal, but each is increasingly more intense than the last. The even movements are nervous scherzi, the first an ostinato, the second more grim and violent. The work’s title, I Feel a Second Heart, refers to a mother sensing her unborn child, and the character of the music makes one wonder just what sort of mother this woman will turn out to be.

The most difficult problem—piano, clarinet, bassoon, and trumpet—fell to Marc André Dalbavie. His solution, inititially, is to create a tumultuous piano part and let the other instruments fend for themselves. This opening gesture repeats with refinements, the downward-cascading piano motif answered more intelligibly (if briefly) by the other burbling instruments. There’s a more static, nocturnal section, with long-held notes from the various instruments and quiet chords in the piano; again, that downward figure is sometimes present, but subtly. A scherzo section maintains a rapid piano ostinato under wind lines that alternately percolate and sail.

The performances all seem authoritative, even in the familiar Debussy sonatas. The flute-viola-harp work is properly atmospheric (the performers are Ransom Wilson, Paul Neubauer, and Heidi Lehwalder); in the cello sonata, the excellent Gary Hoffman and Jeffrey Kahane really capture the whimsy of the middle movement; the Violin Sonata, in the hands of Elmar Oliveira and Jeffrey Kahane, isn’t as bluesy as it might be, and Oliveira’s tone becomes quite grainy when he uses the mute, but it’s a generally satisfactory performance.

The sound quality of these concert recordings is close and a little bright, with the balance somewhat congested in the Dalbavie, but overall presenting the scores and the players to their best advantage. James Reel

Classical Music,

November 18th 2008 at 8:56 —

c (0) —

K

f

g

k

posted by James Reel

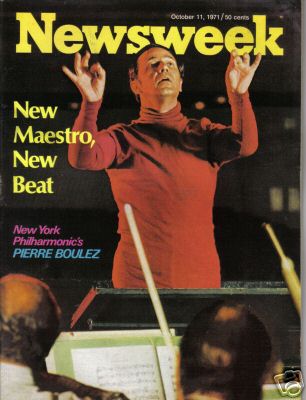

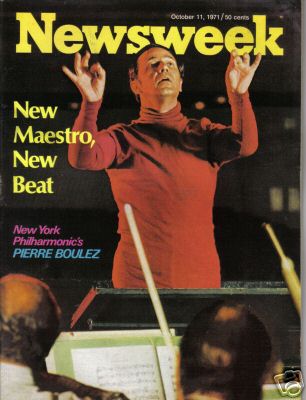

There’s been plenty of talk about how orchestra players should dress on stage, but have you given any thought to what conductors wear in rehearsal? Probably not, because that’s something seen only by musicians, not by audience, except in the occasional (and increasingly rare) documentary, or in photos used as fillers in CD booklets. Most famously, Bruno Walter wore a sort of precursor to the Nehru jacket, familiar from many of his album covers:

Walter’s contemporaries tended to wear white shirts and ties, as did the musicians in rehearsal, but things began to loosen up in the 1960s. Get a load of this out-of-character orange outfit sported by Pierre Boulez in 1971:

And today? Charles Noble, principal violist of the Oregan Symphony, offers a few observations in this post.

Classical Music,

November 17th 2008 at 8:32 —

c (0) —

K

f

g

k

posted by James Reel

This week’s New Yorker cover by Bob Staake is especially striking for the way it blends several common images into an immediately recognizable message, even if that message is a bit hard to articulate. Bear with me, because this post will really be about music, but first look at the image:

That glowing building, of course, is the Lincoln Memorial, which all Americans should be able to identify even without seeing the sculpture of Lincoln inside (which you can’t, really, in this illustration). Overhead, the O in “New Yorker” has been transformed into a softly glowing moon, but it also evokes the O that Barack Obama used as his logo during the presidential campaign:

The implied message: The long night in America for people of African ancestry has nearly ended, a century and a half after Abraham Lincoln ended slavery, with the election of Barack Obama to the presidency.

This got me to thinking about how difficult it can be to craft a message like this through music. You’d think it would be easy; Bob Staake, for his illustration, selects, organizes and layers various symbolic images to create an implicit message, and the same technique should be available to composers through the manipulation of melodies. But it rarely works out that way.

When the technique has been attempted at all, it’s usually merely an act of placing two pre-existing themes in direct opposition to simulate warring nations: think of Beethoven’s Wellington’s Victory, with its conflicting French and English military tunes, or Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture. Of course, Charles Ives was a master of musical collage, but when he piled half a dozen popular American songs and marches upon each other in different meters, tempi and dynamics, he was simply evoking, say, the sounds in a park at night, with music drifting in from various locations. Ives was composing musical landscapes, not really telling a coherent story or making a philosophical point.

Film composers do this routinely, of course, establishing themes to represent specific characters or places or even issues, then manipulating them to underline the complexities of the scene at hand. But right now I’m more interested in concert-hall composers who can’t lean on the crutch of cinematic visuals.

The obvious place for a working-out of symbolic musical themes is the development section of a symphony, sonata or chamber work. Generally, the composer has laid out two or more distinct themes, and then rips them apart and knocks pieces of them against each other before putting things back in order for a recapitulation of the themes more or less in their original form. But this is a very abstract process. Composers may try to create a more concrete message by appropriating melodies that people know from other contexts, but somehow this usually sounds hokey. And if the composers use wholly original material, the themes really have no meaning for listeners beyond the context of the work at hand.

Yet one big exception came immediately to my mind, and you can probably think of a few others. The first movement of Carl Nielsen’s Symphony No. 5 does exactly what Bob Staake does on that New Yorker cover, but with entirely original motifs. Think about the climax in the development of the symphony’s first movement, a grand conflict between three distinctive motifs: an oppressive snare drum motto, a nattering and strident woodwind figure, and a broad, noble hymn. Nielsen wrote this shortly after World War I, and although he did not attach specific meaning to each theme, it’s difficult not to hear this as an explicit war symphony, in which the better angels of our nature (the hymn theme) overcome the destructive forces (which have been overcome, but not eliminated; the snare drum withdraws into the distance at the end, never fully surrendering).

So I’d say that the Nielsen Fifth is a fairly good analog for what’s going on with that New Yorker cover. Do you have other ideas?

Classical Music,

November 14th 2008 at 9:34 —

c (0) —

K

f

g

k