posted by James Reel

If you enjoyed seeing and hearing mezzo Stephanie Blythe in Arizona Opera’s production of The Mikado over the weekend, you’ll be happy to hear that Musical America has named her vocalist of the year. The honor, as usual, seems to recognize ongoing achievement rather than any particular accomplishments during the past 12 months. Here’s what the press release says about her:

“Mezzo-soprano Stephanie Blythe is a singer of extraordinary versatility, an artist who makes the most difficult challenges seem easy, with a big, warm, well-balanced tone throughout an exceptional range. Her latest roles in 15 years at the Metropolitan Opera will be Gluck’s Orfeo in January and Jezibaba in Dvorák’s _Rusalka_ in March, and next summer she sings the roles of Fricka and Waltraute in Seattle Opera’s production of Wagner’s Ring cycle.”

You can read a compact bio of her here, and find out who else got the nod from Musical America here.

Classical Music,

November 19th 2008 at 8:14 —

c (0) —

K

f

g

k

posted by James Reel

If you’re enjoying our Thursday broadcasts of the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center, you might be interested in reviews of a couple of the organization’s downloads I wrote for Fanfare magazine:

BARTÓK Contrasts DVORÁK Piano Quintet in A, Op. 81 Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 477 7073 (digital download only; available at www2.deutschegrammophon.com and www.iTunes.com: 58:07)

DEBUSSY AND THE MODERNS Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 477 6627 (digital download only; available at www2.deutschegrammophon.com and www.iTunes.com: 95:50)

DEBUSSY Sonatas: for Flute, Viola, and Harp; for Cello and Piano; for Violin and Piano STUCKY _Sonate en Forme de Preludes_ SAARIAHO _Je sens un deuxième Coeur (I Feel a Second Heart)_ DALBAVIE _Axiom_

These two early items in the DG Concerts series of downloads (not available on disc) have been available for more than a year, but they’re still worth bringing to your attention, particularly the Debussy project. I’ve coupled them in a single review because if you prefer to transfer your downloads to disc rather than just play them from your hard drive or mp3 device, they fill up a pair of CDs nicely, whereas the first program is too short for one disc and the other is too long.

I’ll make quick work of the first pairing. Contrasts, played by Erin Keefe, Jose Franch-Ballester, and Gilles Vonsattel, benefits from a sometimes bluesy feel in the violin and properly acerbic playing in the clarinet’s high register; the finale has lots of paprika. The Dvorák (performed by Yoon Kwon, Erin Keefe, Beth Guterman, Efe Baltacigil, and Wu Han) receives an ardent performance but one not as high-strung as American ensembles can be these days. The cellist plays with a singing tone, and pianist Wu Han offers many pearly passages. There’s gentle animation where needed in the slow movement, the third balances playfulness with lyricism, and the final movement begins as a scamper, then gradually builds force and power. Both performances hold up very well against the competition, although detailed comparisons seem a bit beside the point if you’re downloading this material for casual listening.

In 1915, Claude Debussy planned to pay tribute to his French Classical forebears (they were really Baroque, but the French hated that term) with a set of six sonatas for diverse instruments. He lived to complete only three, masterpieces all; early in this century, a consortium including the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln center asked three of today’s leading composers to complete the project, using Debussy’s instrumentation but writing in their own style. The new pieces were premiered in 2004, but not until two years later were they presented in the context of Debussy’s own work, and this is a recording of that concert. Each of the new pieces follows one of Debussy’s sonatas, providing many opportunities for comparison and contrast, particularly of how the four composers approach timbre.

At this point, with many recordings of the Debussy sonatas already available, the new works are of greatest interest, so I’ll begin there. Debussy set a real challenge in planning a sonata for harpsichord, oboe, and horn, and Steven Stucky took it on in the form of brief preludes that tend to keep the oboe and horn isolated from each other, not overwhelming the harpsichord. Interestingly, the presence of the harpsichord does not lead Stucky down the Neoclassical path; he offers essentially a series of short conversations between the blown instruments, with the harpsichord indulging in rolled chords and lots of passagework that never sounds like “sewing-machine music.” Each movement has a fanciful title, and the musical material ranges from the largely static “Pierrot Hides in the Shadows” to the comparatively hyperactive “Fireworks.”

One of today’s experts in timbrel possibility is surely Kaija Saariaho, yet she was assigned the relatively conventional combination of piano, viola, and cello. The odd movements in this five-movement suite are nocturnal, but each is increasingly more intense than the last. The even movements are nervous scherzi, the first an ostinato, the second more grim and violent. The work’s title, I Feel a Second Heart, refers to a mother sensing her unborn child, and the character of the music makes one wonder just what sort of mother this woman will turn out to be.

The most difficult problem—piano, clarinet, bassoon, and trumpet—fell to Marc André Dalbavie. His solution, inititially, is to create a tumultuous piano part and let the other instruments fend for themselves. This opening gesture repeats with refinements, the downward-cascading piano motif answered more intelligibly (if briefly) by the other burbling instruments. There’s a more static, nocturnal section, with long-held notes from the various instruments and quiet chords in the piano; again, that downward figure is sometimes present, but subtly. A scherzo section maintains a rapid piano ostinato under wind lines that alternately percolate and sail.

The performances all seem authoritative, even in the familiar Debussy sonatas. The flute-viola-harp work is properly atmospheric (the performers are Ransom Wilson, Paul Neubauer, and Heidi Lehwalder); in the cello sonata, the excellent Gary Hoffman and Jeffrey Kahane really capture the whimsy of the middle movement; the Violin Sonata, in the hands of Elmar Oliveira and Jeffrey Kahane, isn’t as bluesy as it might be, and Oliveira’s tone becomes quite grainy when he uses the mute, but it’s a generally satisfactory performance.

The sound quality of these concert recordings is close and a little bright, with the balance somewhat congested in the Dalbavie, but overall presenting the scores and the players to their best advantage. James Reel

Classical Music,

November 18th 2008 at 8:56 —

c (0) —

K

f

g

k

posted by James Reel

There’s been plenty of talk about how orchestra players should dress on stage, but have you given any thought to what conductors wear in rehearsal? Probably not, because that’s something seen only by musicians, not by audience, except in the occasional (and increasingly rare) documentary, or in photos used as fillers in CD booklets. Most famously, Bruno Walter wore a sort of precursor to the Nehru jacket, familiar from many of his album covers:

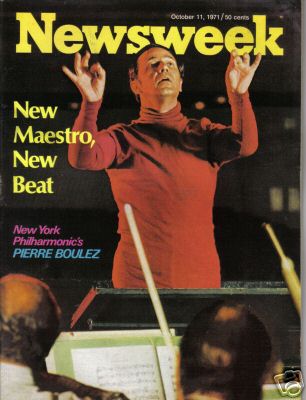

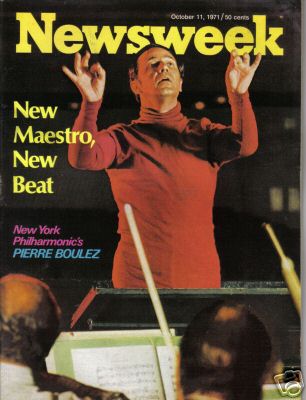

Walter’s contemporaries tended to wear white shirts and ties, as did the musicians in rehearsal, but things began to loosen up in the 1960s. Get a load of this out-of-character orange outfit sported by Pierre Boulez in 1971:

And today? Charles Noble, principal violist of the Oregan Symphony, offers a few observations in this post.

Classical Music,

November 17th 2008 at 8:32 —

c (0) —

K

f

g

k

posted by James Reel

This week’s New Yorker cover by Bob Staake is especially striking for the way it blends several common images into an immediately recognizable message, even if that message is a bit hard to articulate. Bear with me, because this post will really be about music, but first look at the image:

That glowing building, of course, is the Lincoln Memorial, which all Americans should be able to identify even without seeing the sculpture of Lincoln inside (which you can’t, really, in this illustration). Overhead, the O in “New Yorker” has been transformed into a softly glowing moon, but it also evokes the O that Barack Obama used as his logo during the presidential campaign:

The implied message: The long night in America for people of African ancestry has nearly ended, a century and a half after Abraham Lincoln ended slavery, with the election of Barack Obama to the presidency.

This got me to thinking about how difficult it can be to craft a message like this through music. You’d think it would be easy; Bob Staake, for his illustration, selects, organizes and layers various symbolic images to create an implicit message, and the same technique should be available to composers through the manipulation of melodies. But it rarely works out that way.

When the technique has been attempted at all, it’s usually merely an act of placing two pre-existing themes in direct opposition to simulate warring nations: think of Beethoven’s Wellington’s Victory, with its conflicting French and English military tunes, or Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture. Of course, Charles Ives was a master of musical collage, but when he piled half a dozen popular American songs and marches upon each other in different meters, tempi and dynamics, he was simply evoking, say, the sounds in a park at night, with music drifting in from various locations. Ives was composing musical landscapes, not really telling a coherent story or making a philosophical point.

Film composers do this routinely, of course, establishing themes to represent specific characters or places or even issues, then manipulating them to underline the complexities of the scene at hand. But right now I’m more interested in concert-hall composers who can’t lean on the crutch of cinematic visuals.

The obvious place for a working-out of symbolic musical themes is the development section of a symphony, sonata or chamber work. Generally, the composer has laid out two or more distinct themes, and then rips them apart and knocks pieces of them against each other before putting things back in order for a recapitulation of the themes more or less in their original form. But this is a very abstract process. Composers may try to create a more concrete message by appropriating melodies that people know from other contexts, but somehow this usually sounds hokey. And if the composers use wholly original material, the themes really have no meaning for listeners beyond the context of the work at hand.

Yet one big exception came immediately to my mind, and you can probably think of a few others. The first movement of Carl Nielsen’s Symphony No. 5 does exactly what Bob Staake does on that New Yorker cover, but with entirely original motifs. Think about the climax in the development of the symphony’s first movement, a grand conflict between three distinctive motifs: an oppressive snare drum motto, a nattering and strident woodwind figure, and a broad, noble hymn. Nielsen wrote this shortly after World War I, and although he did not attach specific meaning to each theme, it’s difficult not to hear this as an explicit war symphony, in which the better angels of our nature (the hymn theme) overcome the destructive forces (which have been overcome, but not eliminated; the snare drum withdraws into the distance at the end, never fully surrendering).

So I’d say that the Nielsen Fifth is a fairly good analog for what’s going on with that New Yorker cover. Do you have other ideas?

Classical Music,

November 14th 2008 at 9:34 —

c (0) —

K

f

g

k

posted by James Reel

Hi! Remember me? Don’t tell me you didn’t notice I was gone. I took a long weekend to spirit my wife away to California to visit friends and guzzle Napa Valley wine. Now I’m back and settled in, but because I was away I didn’t contribute anything to the latest Tucson Weekly, so I won’t even post a link to that publication because why would you want to read it if I’m not in it?

More seriously, I ran across an interview with Dan Savage, the editorial of an alt weekly in Seattle and the author of the notorious sex-advice column “Savage Love,” which is carried by many alt weeklies, including Tucson’s. Most of the interview concerns his work as a sex columnist, and you should not click on that link if you are proudly prudish. But toward the end, Savage offers some provocative commentary on the advantages of alt weeklies over mainstream dailies. Here’s the essential stuff, but be forewarned that he uses the f-word:

I think alt-weeklies have more and more of a role to play—particularly as dailies continue to try and swim around with an anvil under each arm. One anvil is objectivity and the other is "family newspaper." Alt-weeklies have the luxury of publishing writing by adults, to adults, and for adults. And that's a real advantage. It's a style advantage, it's an attitudinal advantage, and it's also an urban advantage. …

Alt-weeklies are really just about advocacy journalism and truth-telling, and they engage in arguments and throw bombs in the way that daily papers can't allow themselves to. I mean, daily newspapers all need to put "fuck" in a headline above the fold one day—it'll solve all their problems. That's my prescription. And then in one fell swoop they'll get rid of all those 80-year-old subscribers who won't let them drop "Blondie." Catering to the 80-year-olds? Where's that getting newspapers? Making sure there's nothing in your paper that's inappropriate for an eighty-year-old to read?

quodlibet,

November 13th 2008 at 8:28 —

c (0) —

K

f

g

k

posted by James Reel

In the latest Tucson Weekly, I review very good productions of newish plays with local connections. First, what you might call a “found” work:

Two years ago, after viewing a video of a New York production of the musical stage work _Lost_, I peered into my crystal ball and declared, "Arizona Onstage Productions could surely do a brilliant job with the material." (See "Finding 'Lost,' Nov. 9, 2006.)

I was right. The company has mounted a heartfelt production of this dark fairy tale, scored by former Tucsonan Jessica Grace Wing.

In her 20s, Wing moved to New York, where she directed short films and wrote off-Broadway theater scores. In 2003, barely into her 30s, she succumbed to colon cancer, but not before completing _Lost_; she worked on it until literally hours before she died.

Less than a month later, _Lost_ was mounted in New York to highly favorable reviews, but it seems that it had not been performed in the intervening five years. The available libretto and lyrics didn't reflect changes made for the New York International Fringe Festival production, and the orchestration, which Wing didn't have time to complete to her satisfaction, needed work.

Arizona Onstage's Kevin Johnson and his team fashioned a new edition, polishing the orchestration until the afternoon of last week's Tucson opening. Now the work is in shape to travel from one company to another, and it certainly deserves to.

You can read the full review here, and then proceed to my evaluation of a new play by Tucsonan Gavin Kayner:

Are we defined by our stories, or by our actions?

That's a question posed by a character in the new Gavin Kayner play _Noche de los Muertos_, set toward the end of the Mexican revolutionary period. The storytellers are adherents to the Catholic church; the men and women of action are the secularists behind the revolution. Which of those two forces, incompatible when pushed to their heights of fervor, would set the course for 20th-century Mexico?

_Noche de los Muertos_ is the latest offering from Beowulf Alley Theatre Company, and it opened just in time for the Day of the Dead, a time to honor one's ancestors, who are said to visit the altars we prepare and nibble on the snacks we leave, although, unlike Santa Claus and the Easter Bunny, they leave nothing in return; having given life to us some decades before seems a sufficient enough gesture.

_Noche_ is set on the Day of the Dead in 1927 in the town of Magdalena, not far south of Nogales. A young schoolteacher and her entourage have arrived to take over public education from the local priest, one of only about 40 in Mexico who have not yet been killed or driven from their posts by the post-revolutionary government and its supporters. But Catholic partisanship remains strong in rural areas and frontier towns like Magdalena, and the priest refuses to give up his post. In his opinion, and that of supporters like the woman who runs the local cantina, it's the teacher who must be driven out.

Learn how Kayner develops his themes and what the Beowulf Alley team does with them here.

tucson-arts,

November 6th 2008 at 7:41 —

c (0) —

K

f

g

k